A couple years ago we discovered that new users were much more likely to be successful with Buffer if they scheduled at least three updates in their first seven days after signing up. We defined success as still being an active user three months after signing up.

In this analysis we’ll revisit the assumptions we made and determine if this “three updates in seven days” activation metric is still appropriate for today. To do that, we’ll examine usage in the first week after signing up for Buffer. We’ll look at the number of posts scheduled, the number of profiles added, and the number of days that users were active. We will again define success as being retained for three months.

Based on some basic exploratory analysis below, I might suggest an activation metric of at least 3 updates created and 2 days active within the first week. Using this definition, approximately 17% of new users end up activating.

Around 26% of users that did not activate were retained for three months, whereas 42% of users that activated were retained. Activated users are more than 60% more likely to be retained for three months by this definition.

Data Collection

We’ll want to gather all users that signed up before three months ago. We don’t yet know if users that signed up in the past three months were “successful” or not. We also want to know how many profiles they added in the first week and how many updates were created. We want users that signed up between December 1, 2016 and December 1, 2017.

We’ll gather that data with the following query.

with profiles as (

select

u.user_id

, count(distinct p.id) as profiles

from dbt.users as u

left join dbt.profiles as p

on u.user_id = p.user_id and datediff(day, u.created_at, p.created_at) < 7

where u.created_at >= '2016-12-01' and u.created_at <= '2017-12-01'

group by 1

),

last_active_date as (

select

user_id

, max(date(created_at)) as last_active_date

from dbt.updates

where was_sent_with_buffer

and status != 'failed'

and created_at > '2016-12-01'

and client_id in (

'5022676c169f37db0e00001c', -- API and Extension

'4e9680c0512f7ed322000000', -- iOS App

'4e9680b8512f7e6b22000000', -- Android App

'5022676c169f37db0e00001c', -- Feeds

'5022676c169f37db0e00001c', -- Power Scheduler

'539e533c856c49c654ed5e47', -- Buffer for Mac

'5305d8f7e4c1560b50000008' -- Buffer Wordpress Plugin

)

group by 1

)

select

u.user_id

, date(u.created_at) as signup_date

, p.profiles

, l.last_active_date

, count(distinct up.id) as updates

, count(distinct date(up.created_at)) as days_active

from dbt.users as u

left join dbt.updates as up

on (u.user_id = up.user_id and datediff(day, u.created_at, up.created_at) < 7)

left join profiles as p

on u.user_id = p.user_id

left join last_active_date as l

on u.user_id = l.user_id

where u.created_at >= '2016-12-01' and u.created_at <= '2017-12-01'

and (up.was_sent_with_buffer = TRUE or up.was_sent_with_buffer is null)

and (up.status != 'failed' or up.status is null)

group by 1, 2, 3, 4Great, we now have around 1.4 million Buffer users to analyze!

Data Tidying

We also want to know if the user was successful. We do this by determining if the user was still active 90 days after signing up. If the user didn’t send any updates, we’ll set their last_active_date to the signup_date value.

# set last active date

users$last_active_date[is.na(users$last_active_date)] <- users$signup_date

# determine if user was successful

users <- users %>%

mutate(successful = as.numeric(last_active_date - signup_date) >= 90)Let’s see what proportion of signups were retained for three months.

# get success rate

users %>%

group_by(successful) %>%

summarise(users = n_distinct(user_id)) %>%

mutate(percent = users / sum(users))## # A tibble: 2 x 3

## successful users percent

## <lgl> <int> <dbl>

## 1 F 1028578 0.715

## 2 T 410653 0.285Around 29% of users were retained for three months.

Searching for Activation

Now let’s see how well these metrics correlate with success. To do so, we’ll use a logistic regression model.

# define logistic regression model

mod <- glm(successful ~ profiles + updates + days_active, data = users, family = "binomial")

# summarize the model

summary(mod)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = successful ~ profiles + updates + days_active,

## family = "binomial", data = users)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -5.6509 -0.8173 -0.7784 1.4191 2.8803

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.1041152 0.0025668 -430.157 <2e-16 ***

## profiles 0.0651174 0.0013520 48.163 <2e-16 ***

## updates -0.0002771 0.0000295 -9.394 <2e-16 ***

## days_active 0.1143397 0.0012843 89.028 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 1721077 on 1439230 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 1706614 on 1439227 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 1706622

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 5All three metrics seem to have very significant effects on the probability of a user being successful. Interesting, the correlation between updates and success is negative! I have a hunch that this is because of outliers, folks that send thousands of updates in their first days. Let’s remove them from the dataset.

# find quantiles for updates

quantile(users$updates, probs = c(0, 0.5, 0.99, 0.995, 0.999))## 0% 50% 99% 99.5% 99.9%

## 0 0 75 117 414The 99th percentile for updates created in the first week is 75 and the 99.5th percentile is 117, so let’s remove users that created 120 or more updates in their first week.

# remove outliers

users <- filter(users, updates < 120)Now let’s rebuild the model.

# define logistic regression model

mod <- glm(successful ~ profiles + updates + days_active, data = users, family = "binomial")

# summarize the model

summary(mod)##

## Call:

## glm(formula = successful ~ profiles + updates + days_active,

## family = "binomial", data = users)

##

## Deviance Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -3.8116 -0.7995 -0.7807 1.4352 1.6600

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

## (Intercept) -1.0872522 0.0026230 -414.51 <2e-16 ***

## profiles 0.0552942 0.0014378 38.46 <2e-16 ***

## updates 0.0136422 0.0002267 60.18 <2e-16 ***

## days_active 0.0396148 0.0017628 22.47 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## (Dispersion parameter for binomial family taken to be 1)

##

## Null deviance: 1710867 on 1432247 degrees of freedom

## Residual deviance: 1693257 on 1432244 degrees of freedom

## AIC: 1693265

##

## Number of Fisher Scoring iterations: 4That’s much more like it. :)

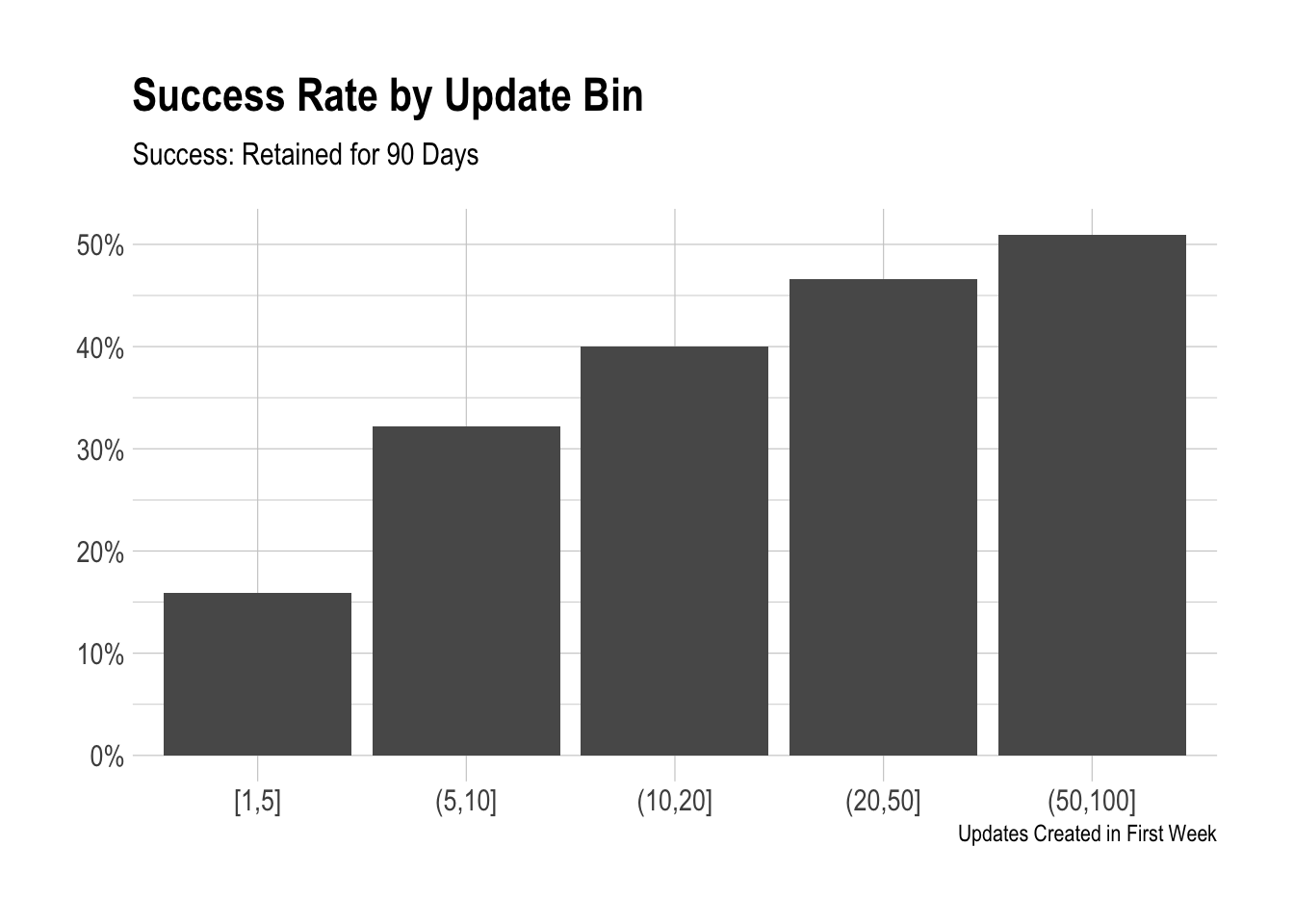

Updates

In the first activation metric, we decided that three updates in seven days was optimal. We can examine the success rate for users that sent a certain number of updates in their first week to help with this.

# define bins

cuts <- c(1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100)

# create update bins

users <- users %>%

mutate(update_bin = cut(updates, breaks = cuts, include.lowest = TRUE))

# plot success rate for each bin

users %>%

group_by(update_bin, successful) %>%

summarise(users = n_distinct(user_id)) %>%

mutate(percent = users / sum(users)) %>%

filter(successful & !is.na(update_bin)) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = update_bin, y = percent)) +

geom_bar(stat = 'identity') +

theme_ipsum() +

scale_y_continuous(labels = percent) +

labs(x = "Updates Created in First Week", y = NULL,

title = "Success Rate by Update Bin",

subtitle = "Success: Retained for 90 Days")

We can see that the success rate increases as the update bins increase. Over 50% of users that create 50 or more updates in their first week are retained for three months. The problem is that there are very few users that do this. We see that there is a big jump from 1 to 20 updates. Let’s zoom in there and see if there is a point with the greatest marginal return.

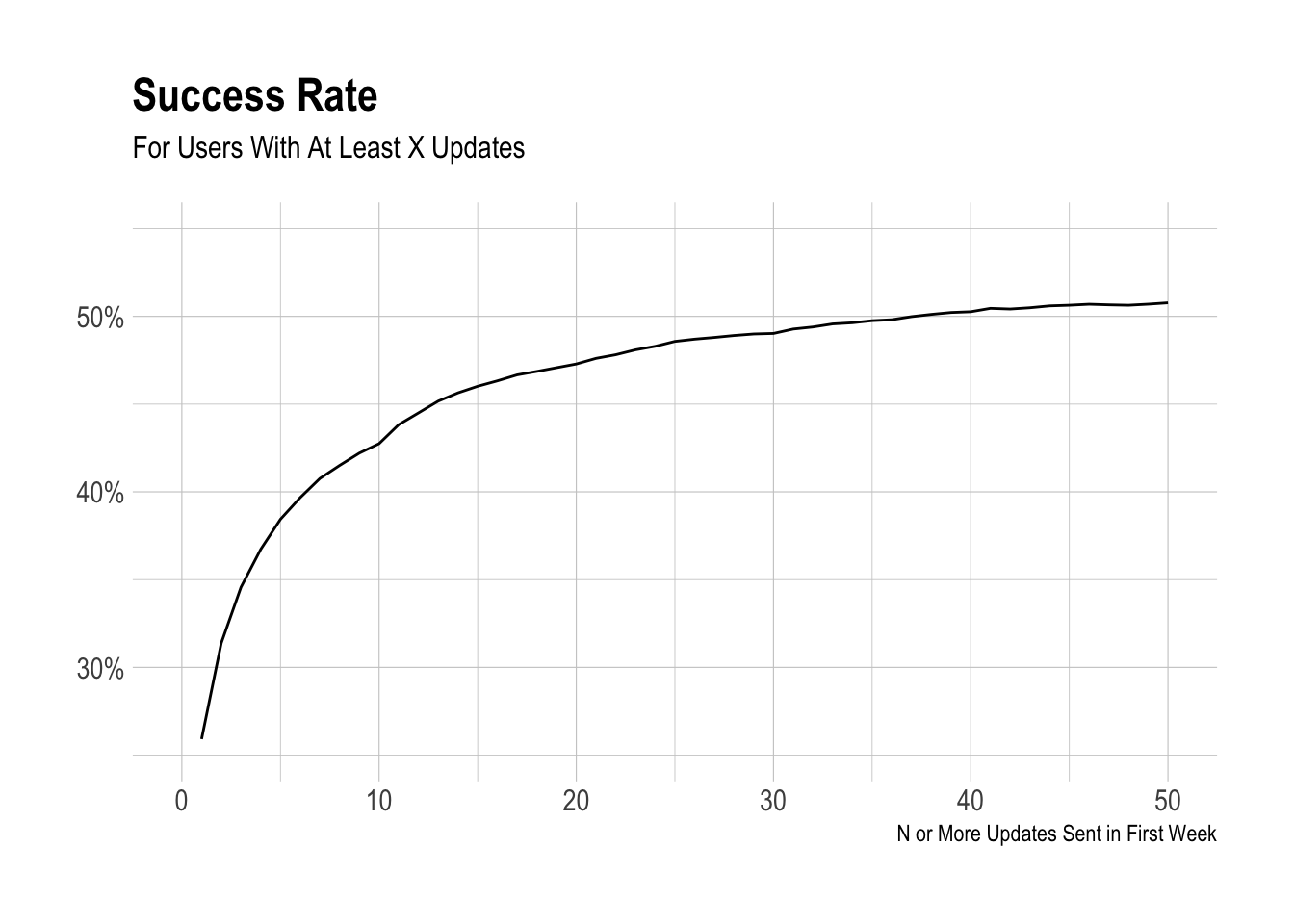

The graph below shows the proportion of users with at least X updates that were reteined for three months. We can see that there are diminishing returns, but it is tough to tell where an inflection point might be. One feature that is cool to see is the little bump at 11 updates. This exists because of the queue limit. Whene a user signs up for Buffer on a free plan, they can only have 10 updates scheduled at one time for a single profile.

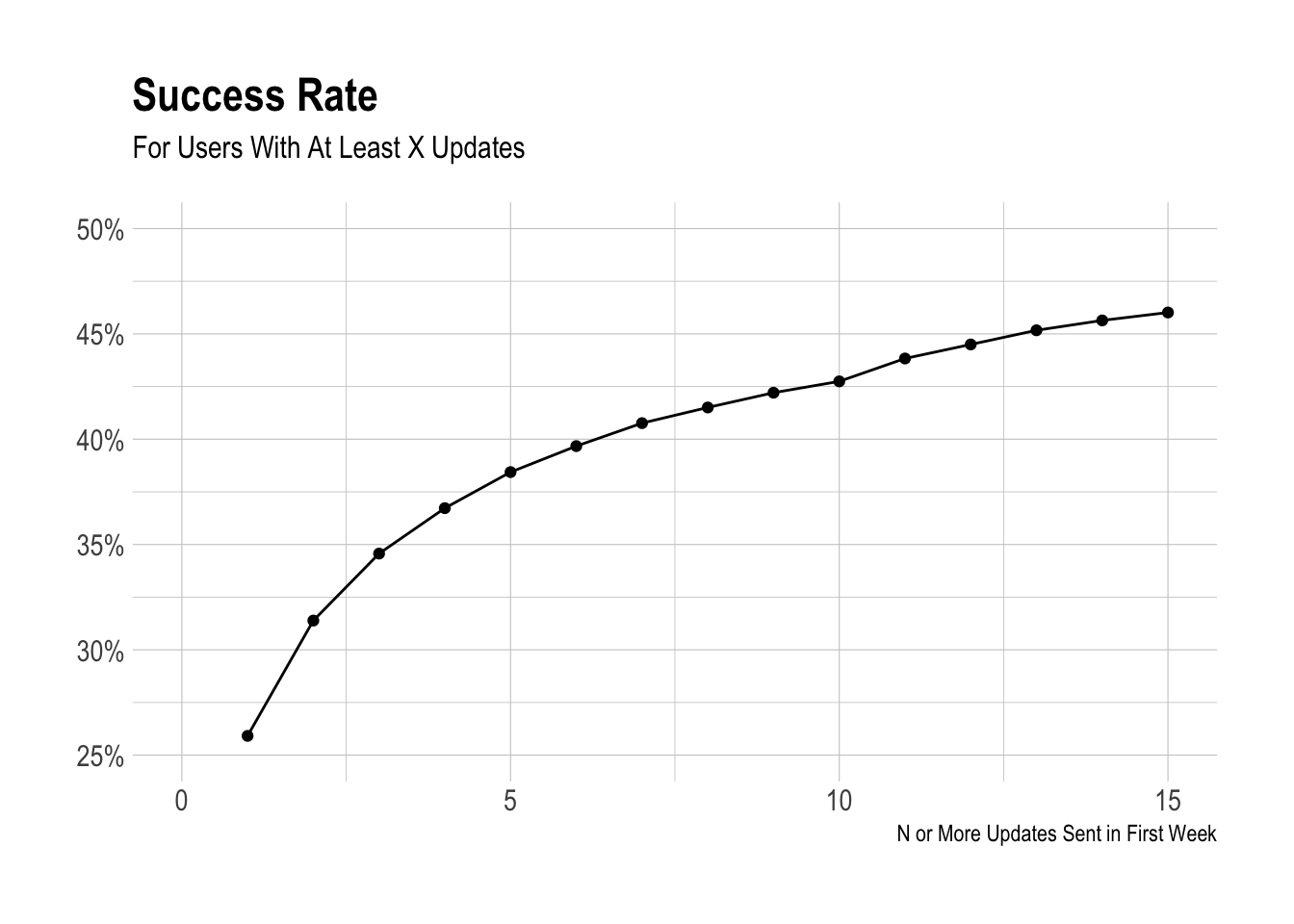

What would this grpah look like if we zoomed into only look at 1-15 updates?

To my eyes, three updates seems as good a choice as any. There are clear diminishing returns after three updates, and a significant number of users (358 thousand) did successfully take the action.

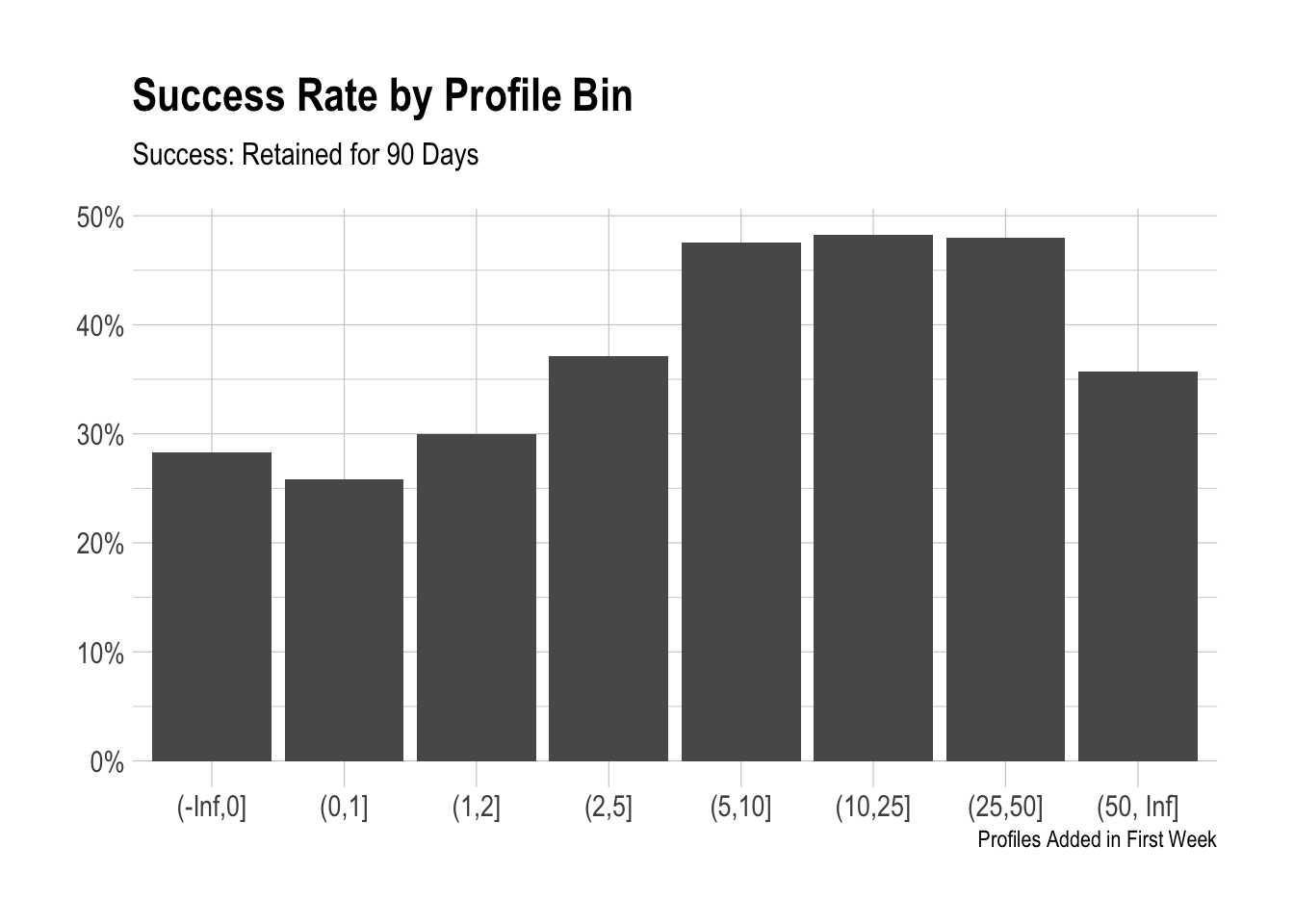

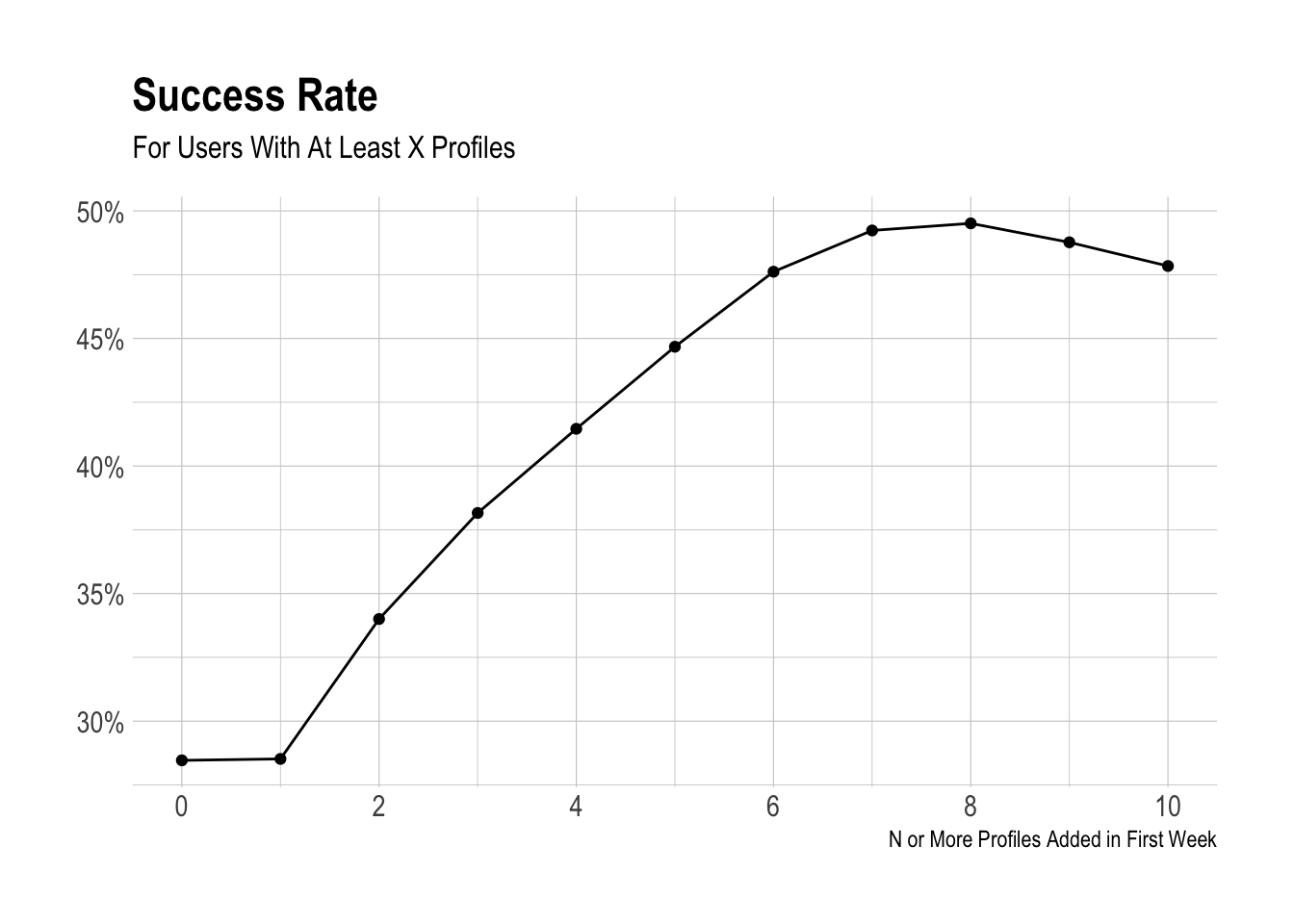

Profiles

We’ll take the same approach to look at profiles.

We can see that adding a single profile doesn’t quite lead to success. The biggest jump in the success rate comes between two and ten profiles.

There don’t appear to be any inflection points here, and we can’t really influence how many social accounts users have in general, so I may not recommend using profiles in an activation metric, despite the strong correlation.

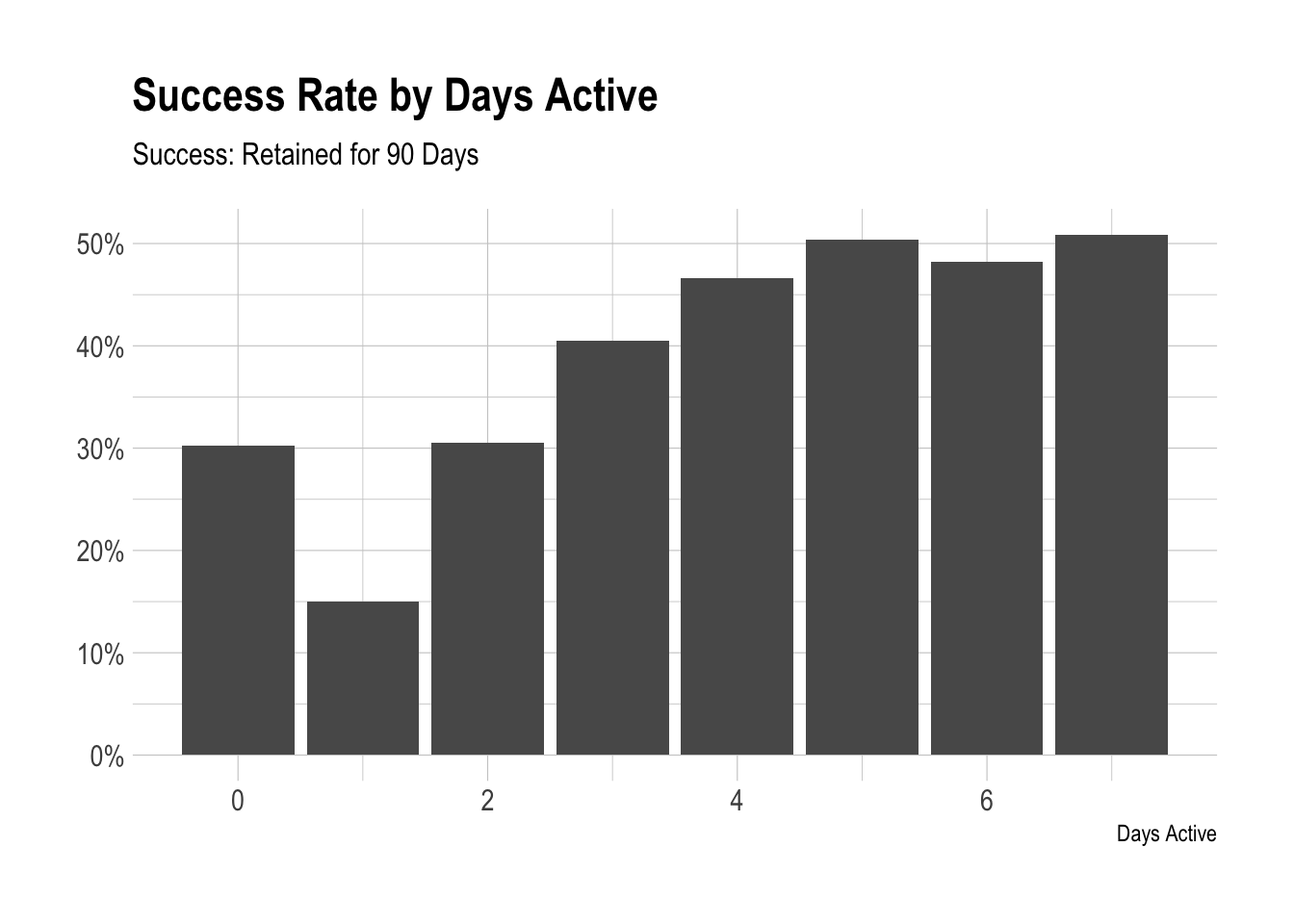

Days Active

Finally we’ll look at the number of days active in the first week. How are there successful users with no days active? These users didn’t send any updates. We’ll have to look into that.

We see a significant jump in the success rate when the number of days active increases from one to two. Therefore, I might suggest an activation metric of at least 3 updates, at least 2 profiles, and at least 2 days active in the first week.

Activation Metric

Let’s see how many users activated, if we use this metric, and what their retention rate was.

# determine if activated

users <- users %>%

mutate(activated = (updates >= 3 & days_active >= 2)) Let’s see the proportion of users that activated.

# get activation rate

users %>%

group_by(activated) %>%

summarise(users = n_distinct(user_id)) %>%

mutate(percent = users / sum(users))## # A tibble: 2 x 3

## activated users percent

## <lgl> <int> <dbl>

## 1 F 1184805 0.827

## 2 T 247443 0.173Around 17% of users activated. Let’s see how likely activated users are to be retained compoared to unactivated users.

# see success rate

users %>%

group_by(activated, successful) %>%

summarise(users = n_distinct(user_id)) %>%

mutate(percent = users / sum(users)) %>%

filter(successful)## # A tibble: 2 x 4

## # Groups: activated [2]

## activated successful users percent

## <lgl> <lgl> <int> <dbl>

## 1 F T 307285 0.259

## 2 T T 100365 0.406Around 26% of users that did not activate were retained for three months, whereas 41% of users that activated were retained. Activated users are more than 60% more likely to be retained for three months by this definition.